Across three millennia, the Aegean and the Arabian Gulf have been maritime crossroads, situated on the same relatively small area of the globe. Greece is often linked to figural sculpture and naturalistic representation; Gulf cultures, especially after Islam, are renowned for calligraphy, geometry, and intricate patterns. Beneath these surface differences, however, lie similarities that extend beyond mere geography: formative mythologies, a focus on order and measure, ideals that structure public space, and the translation of collective memory into durable materials. Here we explore some key parallels from antiquity to the present.

The Aegean and the Gulf:

Parallels in Art, Space,

and Civic Imagination

Map of the region, stretching

from the Mediterranean Sea to

the Arabian Sea

Myth and Poetry

One of the most striking parallels between the two ancient cultures emerges in their respective mythologies and epic narratives. Poetry and oral traditions formed the bedrock of artistic expression in both regions, demonstrating a profound respect for language and its power to convey emotion, history, and wisdom.

Warrior petroglyphs from Bir

Hima site in modern-day Saudi

Arabia, photo by Heritage

Commission

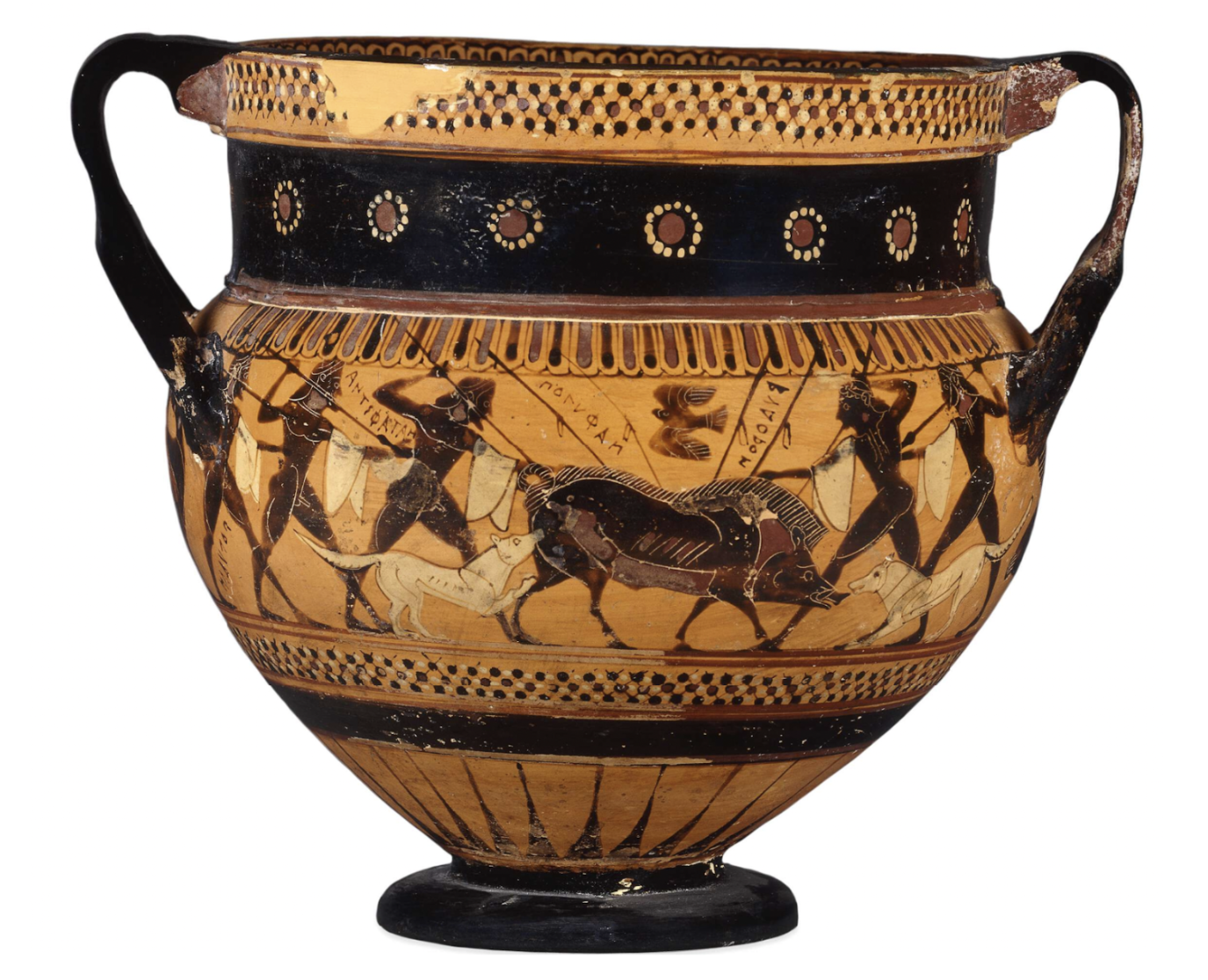

Greek amphora with hunting scene, photo by the British Museum

Ancient Greek society was permeated by a rich pantheon of gods and goddesses, their heroic sagas recounted in Homeric epics like the Iliad and the Odyssey. These tales explored themes of destiny, honor, courage, and the often-fickle nature of divine intervention, shaping moral codes and providing explanations for the natural world. Similarly, pre-Islamic Arabian cultures, and later Islamic societies, developed intricate oral traditions populated by jinn, powerful heroes, and narratives of tribal conquests and moral dilemmas. The epic of Gilgamesh, originating in Mesopotamia, profoundly influenced subsequent narratives in the region, including elements that resonate with later Islamic storytelling. These oral traditions become reflected in more concrete artforms like sculpture, pottery and painting.

Mythical creature excavated

from Mleiha in the UAE,

photo by Sharjah Media bureau

Sphinx of Naxos, photo by

Delphi Archeological Museum

Climate, Materials, and Light

In both regions, the hot, dry summer seasons gave rise to innovative architectural solutions. In Greece, peristyle houses, courtyards, and porticoes temper heat with shade, cross-ventilation, and water. In the Gulf, coral-stone walls, inward-looking courts, mashrabiya screens, and wind towers (barjeel) choreograph air flow and shadow. These are not merely functional devices; they produce a poetics of light.

Chosen materials amplify this interplay with the natural climate: Greek marble, bronze, terracotta (with its now-eroded gilding and polychromy) converted sunlight into symbolic luster; the Gulf’s coral stone, stucco, carved wood, mother-of-pearl, and metalwork similarly draw attention to the light itself. The gloss of bronze in a Greek sanctuary finds an echo in the pearlescent inlay on Gulf chests or the shimmer of glazed tile. In both regions, the sea’s hard light becomes a material itself.

Windtower in Doha, Qatar,

photo by By Diego Delso

Reconstruction of Greek stoa,

photo by:Massimo Pigliucci

Al-Fateh mosque, Bahrain,

photo by Bahrain.com

Order as Aesthetic

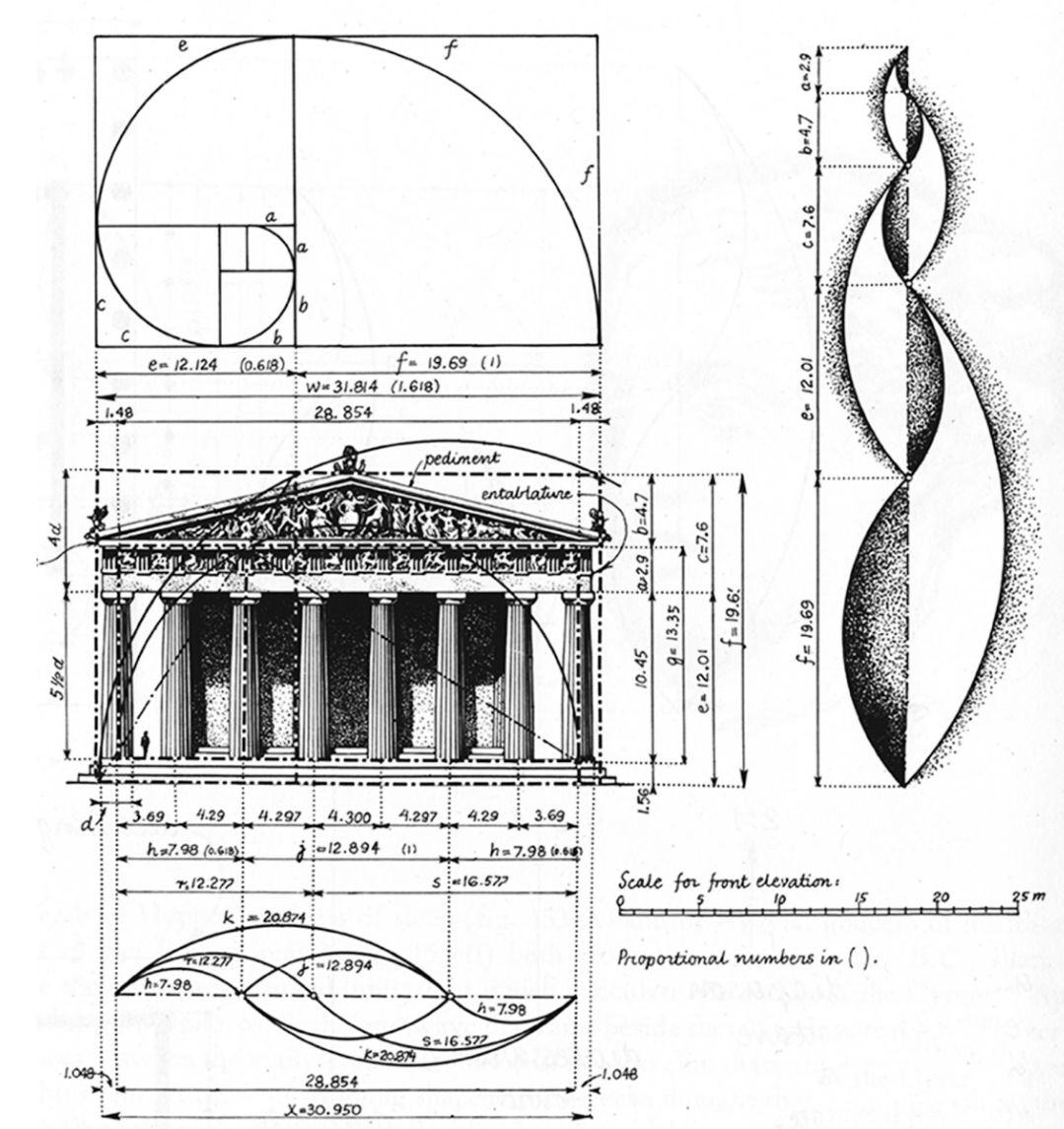

Greek statues and temples encode ratio, rhythm, and symmetry—they are the Pythagorean Theorem made visible. Gulf artistic systems crystallize order through geometry, pattern, and Qur’anic calligraphy, where repetition becomes meditation. One tradition privileges measured ideals; the other translates revelation into the visual logic of line and curve. Yet both aim at order and balance. Epigraphic Greek stelae and Islamic calligraphy—though different in theology and form—share a conviction that text is image and a vessel of memory. In each case, beauty is inseparable from an ethics of proportion: how things should be rightly related.

Bowl with Kufic calligraphy,

photo by Brooklyn Museum

Museum of the Future in Dubai, UAE,

photo by Visit Dubai

Golden ratio in Greek

architecture

Civic Space and Hospitality

In both regions, public life is of great importance. The Greek agora and theater shaped discourse and debate; the Gulf souq, majlis, and Friday mosque organized counsel, exchange, and communal time. For centuries, performance has been central in both cultures: choral drama in one, oral poetry and recitation in the other. Here, art is a civic medium, not a private luxury. A votive statue or honorific stele in a Greek polis taught citizens what was esteemed, while a carved door, Qur’anic inscription, or geometric frieze in a Gulf mosque or merchant house did similar cultural work, binding community to shared values.

An attention to hospitality translates these values into spatial ethics. Greek domestic and civic settings choreograph arrival—a shaded approach, a cool court, a seat. Gulf houses and majlis formalize welcome through thresholds and seating hierarchies, with ritual offerings—water, coffee, bread—echoed in materials and motifs.

The Calligraphy Statue by

Sabah Arbilli, Doha, Qatar,

photo by Islamic Arts Magazine

Courtyard at the Sheikh Zayed

Mosque in Abu Dhabi, UAE,

photo by Wikiemirati

Ancient theatre at Epidaurus,

photo by Carole Raddato

Entrance to Nizwa Fort, Oman

Contemporary Continuities and Technologies

In the present, both regions utilize historic culture to narrate identity. Greece highlights archaeological stewardship alongside a contemporary scene that converses with antiquity—a lineage of artists (including George Petrides) who quote ruins, rework fragments, or probe the politics of memory. Gulf nations have built cultural districts, biennials, and public-art programs, translating calligraphy, geometry, and oral histories into new monumental vocabularies. New commissions reprise ancient patronage with modern tools, like the public sculpture on display in hospitals, campuses, waterfronts, plazas, and transit hubs where daily life unfolds.

Toolsets have changed but the underlying ideals are familiar. Today’s sculptors and architects experiment with scanning, parametric design, CNC, casting, and large-format 3D printing while maintaining the haptic intelligence of clay, plaster, or carving. In both cultures, technology serves human communication and meaning.

Reconstruction of a Greek peristyle

Installation by Dana Awartani (b. Saudi Arabia), Standing by the Ruins, 2019

Sophia Al Maria (b. Qatar),

Black Friday, 2016. Photo by

Ron Amstutz, Whitney Museum

of American Art

Thuraya Al-Baqsami (b. Kuwait),

Return to the Village, 1985.

Photo by the artist.

In Conclusion

To trace parallels is not to erase differences. Greek art keeps human anatomy at the center even as it stretches toward the divine; Gulf art often privileges geometry and pattern as pathways to transcendence. Greek art and Gulf art histories follow distinct theologies and civic traditions. Yet taken together they reveal a shared coastal imagination: civilizations that prize story, balance, and civic belonging—and render those values in durable form. The future of public art in both places lies where it always has: in spaces where people meet and stories circulate.

Head of Thalia II, 2022, Bronze

by George Petrides, Tiffany & Co.

The Landmark, New York